If you’ve ever experienced the sudden onset of the “stomach flu”—with relentless vomiting, watery diarrhea, and cramping—chances are you encountered norovirus. As one of the most common causes of viral gastroenteritis, this highly contagious pathogen has disrupted countless lives, from cruise ship passengers to schoolchildren. Also known as the Norwalk virus (named after the 1968 Ohio outbreak that first isolated it), norovirus targets the digestive system and spreads with alarming speed. Below is a detailed breakdown of its biology, transmission, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention—enhanced with images to clarify key concepts.

What Is Norovirus? Key Biological Traits

Norovirus belongs to the Caliciviridae family of viruses and exhibits unique structural and genetic features that shape its behavior. Only three of its genogroups (GI, GII, GIV) infect humans, and these strains share critical characteristics:

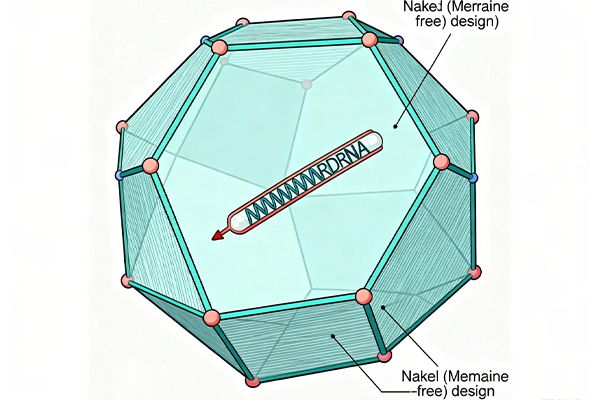

- Naked Icosahedral Capsid: Unlike some viruses, norovirus lacks a lipid membrane (making it “naked”). Its outer shell is an icosahedron—a 20-sided spherical structure made of protein— which protects its genetic material.

- Single-Stranded RNA (ssRNA): The virus’s genome is ssRNA that functions directly as messenger RNA (mRNA). When it invades a host cell (specifically cells in the small intestine), host ribosomes use this mRNA to build a long “polyprotein,” which viral enzymes then split into smaller proteins needed for replication.

How Norovirus Spreads: The “Four Fs” and High-Risk Settings

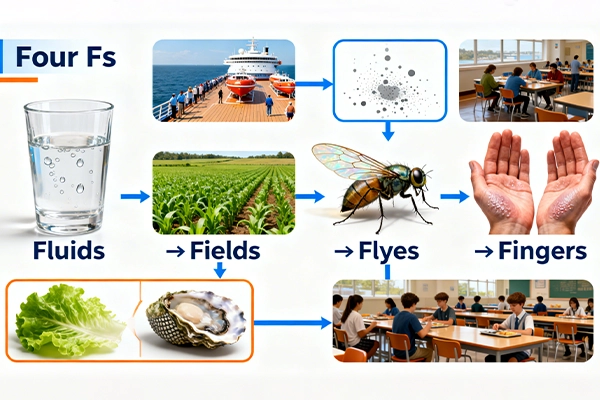

Norovirus is infamously contagious—even a tiny amount of the virus (fewer than 20 particles) can cause infection. Its primary transmission route is fecal-oral, meaning it spreads when people ingest tiny particles of stool from an infected person. This can happen through four common pathways, known as the “Four Fs”:

- Fluids: Contaminated drinking water (e.g., from polluted wells or untreated sources).

- Fields: Contaminated soil or crops (e.g., when infected stool fertilizes agricultural fields).

- Flies: Insects that land on infected waste and transfer particles to food or surfaces.

- Fingers: Hand-to-mouth contact after touching contaminated surfaces (e.g., doorknobs, phone screens, or shared utensils).

The virus also spreads via vomit droplets (released when an infected person vomits) and contaminated food—especially uncooked items like leafy greens and shellfish. It thrives in close quarters, which is why outbreaks often make headlines in:

- Cruise ships

- Nursing homes and hospitals

- Schools and military barracks

- Prisons and athletic team dorms

Symptoms and Complications: When to Worry

After a short incubation period (12–48 hours), norovirus triggers acute gastrointestinal symptoms that typically last 48–72 hours. These symptoms arise from the virus’s damage to the small intestine:

- Vomiting (non-bloody): Caused by slowed food movement through the stomach.

- Watery Diarrhea: Results from impaired absorption of fats and a sugar called d-xylose, plus reduced activity of digestive enzymes (e.g., alkaline phosphatase) in the small intestine.

- Other Symptoms: Abdominal pain, muscle aches (myalgia), headaches, and low-grade fever.

Under a microscope, infected intestinal tissue shows subtle changes: the mucosa (inner lining) remains intact, but the tiny, finger-like projections called villi are blunted, and their even smaller “microvilli” (forming the “brush border” for nutrient absorption) are shortened. Tight junction proteins (which hold cells together) are also damaged, widening gaps between cells.

While most cases are mild, complications can occur:

- Dehydration: The biggest risk, especially in infants, the elderly, and those with chronic illnesses.

- Malnutrition: From prolonged poor nutrient absorption.

- Chronic Gastroenteritis: Rare, but possible in immunocompromised individuals.

Notably, some people stay asymptomatic (no symptoms) but can still shed the virus in their stool for up to 4 weeks—making them silent spreaders.

Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention

Diagnosis

Norovirus is diagnosed using reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)—a lab test that detects the virus’s RNA in a stool sample. This method is highly sensitive and can confirm infection even in mild cases.

Treatment

There is no specific antiviral drug for norovirus. Treatment focuses on supportive care to manage symptoms and prevent dehydration:

- Oral Rehydration Solutions (ORS): Drinks like Pedialyte that replace lost fluids, electrolytes, and sugars.

- IV Fluids: Used in severe cases (e.g., when vomiting prevents oral intake).

- Antiemetics: Medications (e.g., ondansetron) to reduce vomiting (used cautiously, especially in children).

Prevention

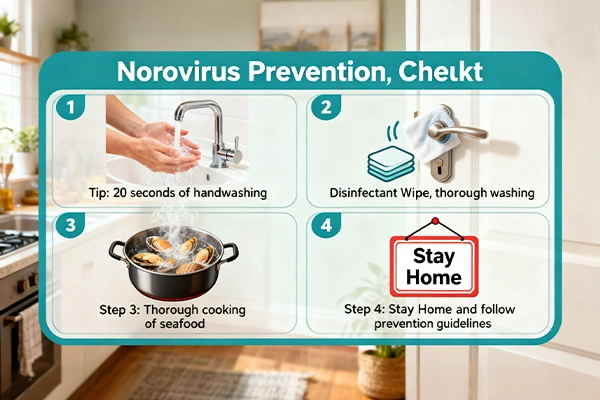

Since there is no vaccine for norovirus, prevention relies on stopping transmission. Key strategies include:

- Handwashing: Use antiseptic soap and water for at least 20 seconds (hand sanitizers with <60% alcohol are less effective against norovirus).

- Surface Sanitization: Clean and disinfect surfaces (e.g., countertops, toilets, phones) with bleach-based cleaners to kill the virus.

- Safe Food/Water: Cook shellfish thoroughly, wash produce with clean water, and avoid drinking untreated water.

- Avoid Close Contact: Stay away from infected people, and keep sick individuals home from work/school.

Final Recap

Norovirus is a ssRNA virus from the Caliciviridae family that causes acute, highly contagious gastroenteritis. It spreads via the fecal-oral route (the “Four Fs”), vomit droplets, and contaminated food/surfaces, targeting the small intestine to disrupt nutrient absorption. Symptoms (vomiting, diarrhea) last 2–3 days, and treatment is supportive. While no vaccine exists, proper handwashing, sanitization, and safe food practices are powerful tools to stop outbreaks. By understanding norovirus’s biology and spread, we can better protect ourselves and our communities.

素晴らしい

Yes