Chances are, you’ve come across the names Ritalin or Adderall. These medications belong to the class of drugs known as stimulants, and they are frequently prescribed to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, commonly referred to as ADHD. At first glance, stimulants and hyperactivity seem like an odd pairing. If someone struggles to sit still, why would we give them a substance that’s supposed to boost energy? The answer, much like with many other psychiatric treatments, lies in a chemical imbalance within the brain. Understanding how stimulants address this imbalance not only sheds light on the root causes of distraction and hyperactivity but also explains why these medications may not provide the expected benefits for those without ADHD.

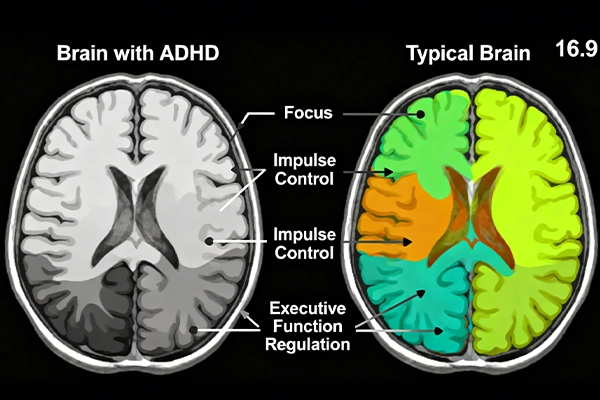

ADHD manifests differently in each individual, but the majority of its symptoms revolve around executive functions—the mental processes that enable us to complete tasks, stay organized, and regulate our behavior. These functions include the traits most commonly associated with ADHD, such as maintaining focus and remembering details. However, symptoms can also extend to difficulties with organization, time management, and controlling impulses and emotions. While scientists haven’t fully unraveled the exact brain mechanisms behind ADHD (studying the human brain directly remains a significant challenge), one leading theory is the low arousal theory. This theory suggests that people with ADHD have chronically underaroused brains, meaning certain brain regions show less activity. This underarousal can occur when neurons in these regions fire less frequently or when neurotransmitters—chemicals that transmit signals between neurons—don’t function properly. According to the low arousal theory, this lack of arousal drives individuals to seek out new stimulation from their environment to “jumpstart” their neural activity. From an outside perspective, this behavior often appears as hyperactivity or inattention.

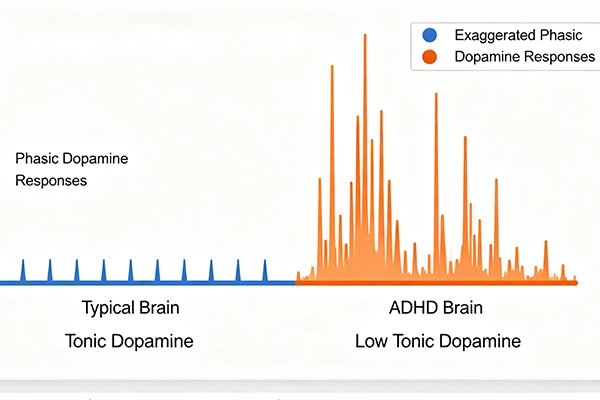

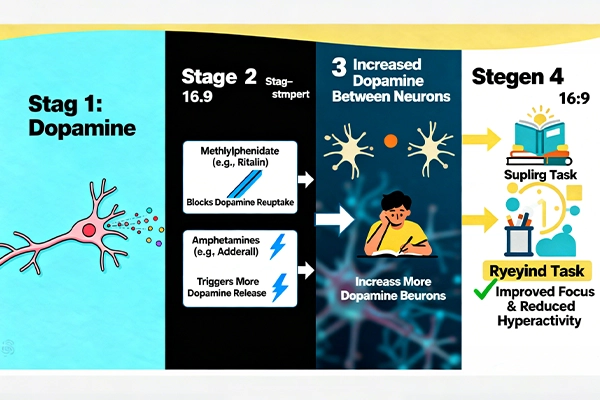

A key neurotransmitter involved in ADHD is dopamine, which plays a crucial role in the brain’s pleasure and reward responses. Generally, higher dopamine levels are linked to a greater sense of reward and well-being. There are two main types of dopamine levels to consider:

- Tonic dopamine: This refers to the baseline amount of dopamine that is constantly present between neurons.

- Phasic dopamine: This is the burst of dopamine released by neurons in response to a specific stimulus—whether it’s finishing a major project, spotting a beautiful bird outside, or even hearing a favorite song.

These two types of dopamine interact closely. For example, high tonic dopamine levels can reduce the strength of phasic dopamine responses. Neurons detect the abundance of dopamine outside the cell and therefore release less when sending signals to the next neuron. In ADHD, the opposite occurs: individuals with the disorder tend to have lower tonic dopamine levels, which amplifies their phasic dopamine responses. While a stronger reward signal might sound beneficial for motivation, it actually leads to hypersensitivity to the environment. The brain craves more stimulation to compensate for the low baseline dopamine, making it nearly impossible to resist dropping a task to explore something new. This constant seeking of novel stimuli often results in hyperactive behavior or difficulty staying focused.

This is where stimulant medications step in. Their primary role is to increase dopamine levels between neurons, reducing the brain’s constant need to seek external stimulation. There are two main categories of stimulants used to treat ADHD:

- Methylphenidate: Found in medications like Ritalin, this drug acts as a dopamine reuptake inhibitor. When a neuron releases dopamine, some of it is not immediately absorbed by the next neuron. Normally, the releasing neuron would “reuptake” this excess dopamine. Methylphenidate blocks this reuptake process, leaving more dopamine available between neurons.

- Amphetamines: Used in drugs such as Adderall and Vyvanse, amphetamines work differently. Instead of blocking reuptake, they stimulate neurons to release more dopamine into the space between cells.

Despite their different mechanisms, both types of stimulants increase tonic dopamine levels, bringing the brain closer to the balanced state seen in individuals without ADHD. As tonic dopamine levels rise, the brain’s arousal increases, and the exaggerated phasic dopamine responses diminish. This reduces the urge to seek external stimulation, making it much easier to focus, stay organized, and control impulses. For many people diagnosed with ADHD, these medications are highly effective, though alternative treatments exist they are generally less impactful.

Unfortunately, the widespread availability of these stimulants has led to recreational use, with some people taking them to enhance study performance or to experience a “high.” This is risky for several reasons. First, both methylphenidate and amphetamines can be addictive, especially when taken in higher doses or more frequently than prescribed. They also carry potential side effects, including sleep disturbances, heart problems, and anxiety. Additionally, for individuals without ADHD, these medications may not actually provide cognitive benefits. While research on this topic is ongoing, reviews published in 2011 and 2012 found only limited evidence of improved mental performance—primarily in simple rote memory tasks, with small improvements that varied by individual. In many cases, any perceived benefit was linked to the placebo effect, where individuals performed better simply because they expected the drug to work. It’s important to note that this research does not definitively prove that stimulants have no benefits for non-ADHD users, and it should never be used as a self-diagnostic tool.

In summary, stimulants help with ADHD not by “giving people more energy,” but by correcting the brain’s chemical imbalance—specifically by increasing tonic dopamine levels. This restores balance to the brain’s reward and arousal systems, reducing hyperactivity and improving focus. For those without ADHD, the risks of side effects and addiction often outweigh any potential benefits, which may be driven more by placebo than actual chemical changes. Understanding the science behind these medications is key to using them safely and effectively, and to debunking misconceptions about their role in treating ADHD.